FIDO2, passkeys, and hardware authenticators

For decades, digital security rested on a fragile assumption: that users could consistently safeguard secrets within increasingly complex systems. Unique, long passwords, rotated periodically and never reused. The problem was not a lack of rules, but the unrealistic expectation of human compliance.

The outcome is well known—and echoes what I discussed in Stop rotating passwords : massive credential reuse, increasingly sophisticated phishing, and “two-factor” mechanisms that, in practice, do not withstand a well-executed attack. A large portion of modern security is still based on secrets that can be copied, intercepted, or socially engineered.

From a technical standpoint, the problem is structural. From a philosophical one, it is even simpler: if something can be copied without friction, it cannot be considered a strong proof of identity.

In recent years, the concept of passkeys

has gained traction—a modern authentication method defined within the FIDO2/WebAuthn

standard. A passkey is not an improved password, but rather an asymmetric cryptographic key pair generated for a specific service, where the private key remains protected on the user’s device (dedicated hardware, operating system, or an external authenticator) and the public key is stored by the service. Authentication is performed through cryptographic signatures and context validation, eliminating the need to share reusable secrets.

This approach is standardized by the FIDO Alliance and adopted by major operating systems and modern browsers.

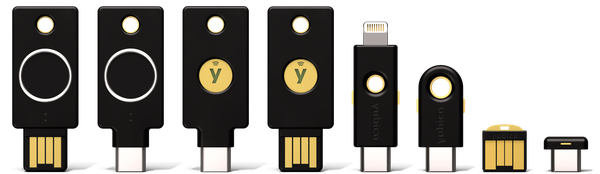

In this context, hardware authenticators emerge as a way to store these passkeys—particularly YubiKeys, which I use in my day-to-day work. Not as a magic solution, but as a paradigm shift: moving from proving knowledge of a secret to proving verifiable possession of a physical object, backed by asymmetric cryptography and validation of the authentication context.

This article does not aim to evangelize or sell devices. The goal is to analyze what real problems hardware authenticators solve, in which scenarios they provide tangible security benefits, and where they simply add unnecessary complexity. Because security is not about piling on controls, but about reducing attack surfaces without losing operational control.

What is a hardware authenticator (and what it is not)?

A hardware authenticator is a physical authentication device designed to prove identity using standard cryptographic mechanisms. It does not store service passwords nor does it act as a generic container for secrets. Its primary function is to prove physical presence and possession of a private key that cannot be extracted from the device.

From a technical standpoint, a hardware authenticator such as a YubiKey implements several open protocols—primarily FIDO2/WebAuthn, but also U2F, OTP, PIV, and OpenPGP depending on the model—which allow a remote system to verify identity without the need to share reusable secrets. The private key never leaves the device; the only thing transmitted is a cryptographic signature generated in response to a specific challenge.

This detail is central: there is no secret that can be copied. Unlike a password or a TOTP code, there is no piece of information that an attacker can intercept and reuse later. Authentication is bound both to the physical device and to the usage context (for example, the web domain requesting authentication).

What a hardware authenticator is

- A physical device that functions as an authenticator based on asymmetric cryptography.

- A proof-of-possession mechanism with verification of physical presence.

- A strong second factor or, in some scenarios, the primary authentication factor.

- A component that can be integrated into modern identity flows, such as Zero Trust or passwordless architectures.

In practical terms, a hardware authenticator shifts the focus of security from “something you know” to “something you have,” dramatically reducing the attack surface associated with phishing and credential theft.

What a hardware authenticator is not

- It is not a password manager.

- It is not a USB flash drive or a clear-text secret store.

- It is not an absolute guarantee of security.

- It does not replace proper access design, monitoring, or incident response.

A hardware authenticator can strengthen a poorly designed system, but it cannot fix structurally weak decisions.

A change in model, not an incremental improvement

The most important difference introduced by a hardware authenticator is not technological, but conceptual. Passwords and many traditional MFA mechanisms are based on shared secrets. Hardware authenticators break away from that model: verification is performed without sharing the secret, and identity is validated through a cryptographic proof bound to a specific physical object.

This shift in approach is what justifies their adoption in environments where identity is a critical asset.

Protocols matter more than hardware

So far, I have been speaking mainly with YubiKeys in mind (and I will continue to do so in this and other articles on the blog, as I said: it is the hardware I use). But treating them as the standard would be a conceptual mistake—security does not reside in the brand, but in the protocols the device implements. YubiKey is relevant because it adopts open, widely supported standards, not because it is a magical artifact. In fact, there are other devices with equivalent compatibility, which I will mention later.

From a technical perspective, the value of a hardware authenticator is determined by two factors:

- which protocols it supports,

- how it implements them.

The device is interchangeable; the protocol is not.

FIDO2 / WebAuthn: the standard that changes the rules

FIDO2, together with WebAuthn, is currently the most relevant protocol for strong authentication. It defines a model based on asymmetric cryptography in which:

- Each service receives a unique key pair.

- The private key never leaves the device.

- Authentication is cryptographically bound to the requesting domain.

- Physical presence is required (and optionally a PIN or biometrics).

This fundamentally eliminates entire classes of attacks such as phishing, replay, credential stuffing, and the theft of reusable password databases.

What matters is not that a YubiKey supports FIDO2, but that any authenticator that implements it correctly inherits these properties.

U2F: old, but still relevant

U2F is the predecessor of FIDO2. Although it is now considered “legacy,” it remains widely supported and, from a security standpoint, is still far superior to TOTP or SMS.

Limitations:

- does not support passwordless authentication

- less flexibility

- more limited policy control

Even so, a well-implemented U2F device remains a real improvement over weak MFA.

OTP and TOTP: useful, but insufficient

Many hardware authenticators offer OTP or TOTP code generation. Technically they work, but conceptually they do not solve the underlying problem:

- they are still reusable secrets

- they are vulnerable to real-time phishing

- they do not validate context or origin

They are an intermediate step, not a final goal. Useful when there is no other option (which is still the case for many services today), but not comparable to FIDO2.

PIV / OpenPGP: more specialized use cases

Some devices support PIV (X.509 certificates / smart cards) and OpenPGP. These modes are very useful in specific contexts: traditional enterprise authentication, code signing, encrypted email, SSH with non-exportable keys, and similar scenarios.

These are considerably more technical use cases, not intended for the average user, but in environments with specific technical requirements, when properly managed, they remain solid tools.

YubiKey is not alone: there are several alternatives

YubiKey is probably the best-known device, but it is not the only one nor a requirement for adopting strong authentication.

There are alternatives of different sizes and profiles, such as:

- SoloKeys

- Nitrokey

- Google Titan

- Thales SafeNet eToken Fusion

And even authenticators integrated into hardware platforms (such as Secure Enclave on Apple devices or built-in FIDO platforms). Even the TPM chip can serve this purpose (Windows Hello uses the TPM when no separate physical authenticator is available).

The reality is that all of these options can be valid if they correctly implement FIDO2/WebAuthn, use open standards, and have stable support across the services being used.

So the right question is not “Which brand should I buy?”, but rather: “Which protocols do I need, and are they available and well supported in my stack?”

So, why is FIDO2 different?

Most authentication mechanisms fail for the reason I mentioned earlier: they rely on reusable secrets. Passwords, OTP codes, TOTP, or magic links are variations of the same pattern. The form changes, but not the nature of the problem: if a secret can be captured or forwarded, it can be exploited.

FIDO2 breaks away from that model. And it does so without adding yet another layer on top of passwords—it directly eliminates the need to share a secret.

Challenge-based authentication, not secrets

In FIDO2, the flow is fundamentally different from the mechanisms mentioned above:

- The service generates a unique cryptographic challenge.

- The authenticator signs that challenge with a private key stored in hardware.

- The service validates the signature using the previously registered public key.

Here is a diagram illustrating this authentication flow:

There is no reusable information, no code that remains valid for a period of time, and nothing to intercept. Each authentication is a unique event, not a repetition of a pre-existing secret.

The domain matters (and this stops phishing)

One of the key aspects of FIDO2 is origin binding. The authenticator validates the domain requesting authentication and will only respond if it matches the domain for which the key was generated.

This has a direct and practical consequence: a fake site can look identical, can use HTTPS, and can even have a valid certificate, but it cannot obtain a valid signature, because it does not control the legitimate domain.

In other words, phishing stops being a “user education” problem mitigated with filters and awareness campaigns, and becomes a technical problem for the attacker. And that is exactly what it should be. This is why FIDO2 is considered a phishing-resistant authentication mechanism.

Verifiable physical presence

FIDO2 requires a physical action from the user: touching the device, entering a PIN, or using biometrics (depending on the authenticator). This introduces a proof of presence that cannot be automated or simulated remotely. The user actively participates in the authentication event.

Unique keys per service

Each service receives a different key pair. This eliminates another long-standing issue: the cascading impact exploited by attacks such as credential stuffing. If one provider is compromised, there are no reusable credentials and no way to move laterally to other services. Compromise is contained by design.

Below is a diagram showing how an authenticator is associated with a service:

FIDO2 as a foundation for passwordless

All of the above enables something that, years ago, was impractical at scale: completely eliminating the password. This is not a theoretical ideal, but a real-world implementation that major providers such as Microsoft are already adopting and driving forward. Passwordless is a natural consequence of a better-designed identity model.

A philosophical reflection

For years, attempts were made to compensate for human weaknesses with more rules, more complexity, and more warnings. FIDO2 proposes the opposite: accepting human limitations and designing the system around them.

It is not about trusting that the user will not fall for a scam. It is about building a system where falling for a scam is not enough to compromise identity. In my view, this is an important and necessary conceptual correction.

Real-world use cases: where a hardware authenticator provides tangible security

Not all systems benefit equally from a hardware authenticator. In some cases the impact is marginal; in others it represents a major leap in identity security. As you can imagine, the difference is not in the technology itself, but in which risk is being addressed.

I am not going to list everything these devices can do, but rather some things that are worth doing. In future articles, I hope to expand on these and other use cases.

Protecting critical accounts

Accounts that allow the recovery of other accounts—primarily email and the password manager—are the logical starting point.

Applying FIDO2 to these services has an immediate effect: phishing becomes unviable, session hijacking is dramatically harder, and the impact of a compromise is reduced.

In this context, with a proper implementation, a hardware authenticator does not act as a “second factor,” but rather as an identity anchor. If the attacker does not have the physical device, access simply does not happen.

Access control for repositories and code

Platforms such as GitHub or GitLab concentrate a growing volume of critical assets: code, pipelines, secrets, tokens, and access to infrastructure.

Using FIDO2 or non-exportable keys for login, commit signing, or access to runners or APIs reduces concrete risks of identity impersonation, supply chain attacks, or the introduction of malicious code with seemingly legitimate authorship.

Access to infrastructure and administrative systems

In server, cloud, or network environments, strong authentication has a clear return on investment.

Some typical use cases include:

- SSH with non-exportable FIDO2 keys

- access bastions

- administrative control panels

- VPS or DNS providers

The difference compared to traditional passwords is fundamental: the secret cannot be copied, even if the system from which access is performed is compromised.

Linux and local system control

This is a case I have used and explored in particular, because on GNU/Linux systems an authenticator can be integrated beyond the browser:

sudowith presence verification- local login via PAM

- unlocking encrypted volumes (LUKS)

- GPG signing from hardware

These use cases are especially relevant on laptops, mobile workstations, or in contexts where physical control is not absolute. They allow you to raise the real cost of a local compromise. It is worth noting that several of these scenarios have their equivalents on Windows systems with Windows Hello and third-party tools.

When it does not provide real value

I believe that understanding when adopting a hardware authenticator is not relevant is just as important as knowing where it does add value.

In general, adopting this type of authentication is not justified for:

- low-impact systems

- ephemeral, non-privileged access

- environments without adequate protocol support

- as a replacement for poorly implemented basic controls

Adding hardware without a clear objective usually introduces friction without improving security.

A practical rule

If an account allows you to:

- recover other accounts

- execute code

- modify infrastructure

- access sensitive data

then strong, hardware-based authentication is justified. If not, probably not.

These devices and passkeys are not meant to be used everywhere, but rather at the points where identity is critical. That is where the model shift introduced by FIDO2 translates into a concrete and measurable security improvement.

Common mistakes and poor decisions

The adoption of hardware authenticators often fails not because of technical limitations, but due to misunderstood decisions. In many cases, the authenticator ends up being a security talisman: it is present, but it does not change the risk model.

Using a single key

This is probably the most common mistake. A device like a YubiKey is a physical object (and a fairly small one). Physical objects get lost, break, or become inaccessible. Using a single key without an alternative recovery method is a recipe for permanent lockout.

Minimum best practices:

- at least two authenticators registered

- one for daily use

- one backup, stored offline

Completely replacing the passphrase without a backup

Removing passwords without a recovery plan turns passwordless into irrecoverable.

For critical services or local encryption, it is important to keep an alternative method (passphrase, recovery key), document the recovery process, and test it before it is actually needed.

Using OTP “because that’s what’s available”

Generating OTP codes from a YubiKey is better than SMS, but it does not change the threat model. The code is still a reusable secret, susceptible to real-time phishing.

This mistake often appears when a service supports FIDO2 but it is not enabled, or when compatibility is prioritized over security. If the protocol does not eliminate the class of attack, the benefit is limited.

Believing FIDO2 replaces other controls

FIDO2 protects identity, not the entire system.

It does not replace:

- monitoring

- compromise detection

- privilege management

- separation of duties

- incident response

An attacker can still be effective if they obtain undue privileges through other means. Strong authentication is a foundation, not a complete defense.

Not understanding which protocol is being used

Many implementations fail due to lack of understanding. Assuming that MFA automatically implies phishing resistance, not distinguishing between different protocols, and assuming all flows are equivalent are common mistakes.

The result is a false sense of security based on labels rather than on the actual properties of the protocol.

Not protecting the recovery channel

The weakest access is often the account recovery mechanism.

Using FIDO2 is of little value if:

- recovery still relies on email + SMS

- downgrading to weak MFA is allowed

- support can reset access without strong verification

Security must be evaluated by the easiest path, not the most robust one.

Introducing friction without a clear objective

In an ideal world, we could adopt strong authentication everywhere. In the real world, adding it to low-impact systems or to access without real privileges often generates rejection and abandonment.

Strong authentication should be applied where the impact of a compromise is high, identity is a critical asset, and the friction is justified.

Conclusion

The most common mistake when talking about security is thinking of it as a sum of controls: more factors, more rules, more warnings. In practice, this often produces systems that are fragile, hard to operate, and easy to bypass via the least expected path.

A more useful mental model starts from a different premise: identity is a system, not a piece of data.

Passwords fail not because they are short or reused, but because they are copyable secrets. It does not matter how often they are rotated or how many factors are added around them; as long as the model depends on something that can be intercepted and reused, the problem remains.

FIDO2 introduces a simple yet profound conceptual correction: identity is not proven by sharing a secret, but by proving possession and context through cryptography. The system does not rely on the user remembering better, but on mathematical properties and on the practical impossibility of copying a physical object or something stored in a cryptographically robust chip.

Hardware authenticators are not a universal solution nor a requirement for every system. Their value emerges when identity becomes a critical asset.

When used correctly, they enable:

- eliminating phishing as an effective attack vector

- reducing the impact of partial compromises

- simplifying complex access models

- enabling passwordless without losing control

When used incorrectly, they become just another layer of friction, with no proportional benefit.

The difference is not in the device, but in how the problem is framed. Adopting FIDO2 is an architectural decision: accepting that systems must be designed around human limitations, not against them. Within that framework, hardware authenticators are not an end in themselves, but a well-defined tool for a specific problem. And like any good tool, their value lies not in owning it, but in knowing exactly when and why to use it.

References

YubiKey 5 Series – Technical Manual

Official documentation on the protocols supported by YubiKey (FIDO2, U2F, PIV, OpenPGP, OTP, etc.).

https://docs.yubico.com/hardware/yubikey/yk-tech-manual/yk5-intro.htmlYubico – Authentication Standards (FIDO2 / WebAuthn)

Overview of the FIDO2 standard and its use for passwordless authentication.

https://www.yubico.com/authentication-standards/fido2/WebAuthn – W3C Recommendation

Official specification of the WebAuthn standard, the technical foundation of FIDO2 and passkeys.

https://www.w3.org/TR/webauthn/FIDO Alliance – Passkeys

Definition and explanation of the passkeys concept within the FIDO2 ecosystem.

https://fidoalliance.org/passkeys/Yubico – WebAuthn Developer Guide

Technical guide to understanding registration and authentication flows with FIDO2/WebAuthn.

https://developers.yubico.com/WebAuthn/WebAuthn_Developer_Guide/IBM – What is FIDO2?

A clear explanation of the FIDO2 model, CTAP, and WebAuthn.

https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/fido2