Zero Trust: Why Trusting Less is a Good Idea

I spent several years selling and implementing ZTNA solutions. Lots of VMware, plenty of Microsoft, some Fortinet. Good products, solid, well-thought-out, with good engineering behind them. The difficult part was almost never the technology—it was explaining what we were trying to solve.

Every now and then I had to give a talk about Zero Trust, or Zero Trust Architecture, or Zero Trust Network Architecture, depending on the audience and the slide deck du jour. If I was lucky, a client would show up afterward saying they wanted to “implement Zero Trust,” and I’d ask them, among other things, what problem they were trying to solve. Sometimes the conversation got interesting: remote access, identities, lateral movement, security strategy. Good. Other times the answer was an uncomfortable silence, or something like: “I want to implement Zero Trust to be secure” and not much more than that.

Zero Trust became just another checkbox on compliance presentations or cybersecurity strategies. And vendors—myself included, no guilt—often didn’t help. We sold it as if it were an appliance, with a pitch of “buy this, deploy that, integrate with whatever, and done.” I’ve seen people who, with a three-month project and a couple of painful migrations, promise you you already have Zero Trust. As if it were a certification that arrives via email.

The reality is different. Zero Trust is not something you buy. It’s not a product, it’s a strategy; a way of thinking about access, the network, and system security. A much more distrustful way, in fact.

The curious thing is that most organizations already have a good part of what’s needed to get started. They don’t call it Zero Trust, they don’t use it coherently with this architecture, but it’s there: identities, basic segmentation, logs, device controls, encryption capabilities, all somewhat dormant.

This article is not a canonical guide or a “best practices” manual—there are no universal recipes. It’s more a summary of what I learned from watching implementations that worked, and others that got stuck halfway. Some with obscene budgets, some with well-integrated technology from a single vendor, others made with effort, patience, and a diverse tech stack. And if I have to summarize: success almost never came from “buying the right solution.” What works is understanding both the architecture and the real problem, making the most of the technology you have, and only then—when it makes sense—going out to buy something new.

What is Zero Trust, Without the Marketing?

Zero Trust boils down to three ideas: never trust by default, always verify, and grant the minimum necessary access. It sounds obvious when you put it that way, but it breaks with thirty years of network design.

The traditional model is the castle and moat. You build a strong perimeter—firewall, VPN, DMZ to expose services—and everything inside is trusted territory. If you made it past the wall, you’re one of us. You segment with VLANs, subnets, some ACLs between zones, but the underlying premise doesn’t change: there’s an “inside” and an “outside,” and inside is safe.

The problem with that model isn’t that it’s bad in itself. For years it worked reasonably well. The problem is that it assumes a well-defined perimeter exists, that it’s airtight, and that those inside are trustworthy. And all three things stopped being true a while ago. Modern attacks generally don’t force the front door; they steal credentials, exploit a vulnerability on a remote endpoint, or simply wait for someone to click in the wrong place. And once inside, with the traditional model they can move laterally without much resistance.

Zero Trust inverts the logic. There’s no trusted “inside.” Every access is validated: who the user is, what device they’re connecting from, what security posture that device has, what resource they’re requesting, and whether they really need to access it. The perimeter is no longer a physical firewall in a rack; it’s mobile, on every endpoint and around every resource.

This means stopping thinking about the “secure internal network” and starting to think something like “every data flow is suspicious until proven otherwise.” It’s uncomfortable, because it forces you to distrust things you used to take for granted—and to have controls for it. But it’s necessary, because in the era of multi-cloud and remote work, threats no longer respect the border you drew on the network diagram.

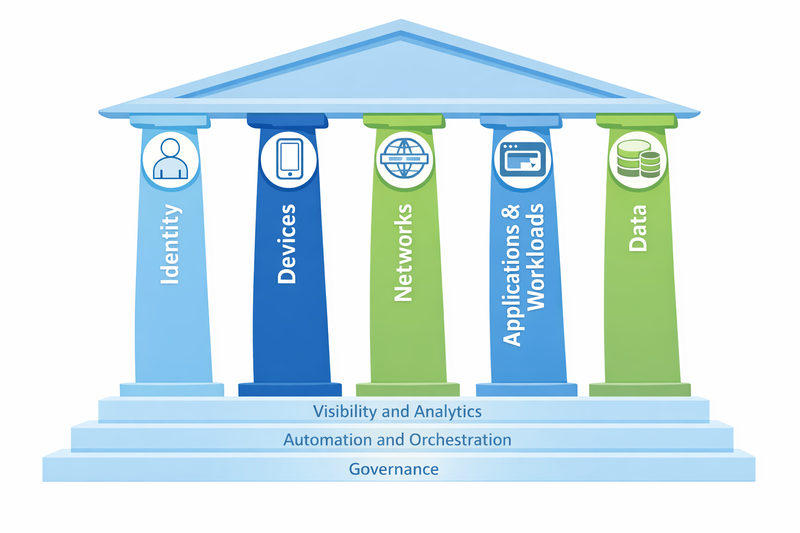

The 5 Pillars

Zero Trust is not a single technology, but a set of network and security architecture principles supported by five interdependent pillars. Each protects a different aspect of the access flow, but none works in isolation. The strength lies in how they integrate.

Let’s look at each one: what they protect, how they work at a high level, how they interact with other pillars, and some examples of tools that provide required functionalities for each pillar.

Device Trust (the Device as a Verifiable Actor)

What it protects: Prevents compromised, outdated, or unauthorized devices from accessing corporate resources. A valid user on an untrusted device is still a risk.

How it works: The device must prove its identity and security posture before allowing any access. This is achieved through:

- Unique identification: Machine certificates that function as “device credentials.” It’s not enough to know that “someone” is connecting; you need to know from which specific device.

- Posture checking: Before authorizing access, the system validates that the device meets minimum requirements: active antivirus, enabled firewall, patched OS, no jailbreak/root, encrypted disk, etc. If something fails, access is denied or restricted.

- Inventory and registration: Only explicitly authorized devices can attempt to connect. Unregistered BYOD doesn’t get in.

Integration with other pillars:

- Combines with User Trust to validate not only “who you are” but “where you’re connecting from.” Stolen credentials on a non-corporate device aren’t enough.

- Feeds into Application Trust: the gateway can decide to grant access to less critical apps from any corporate device or authorized BYOD, but restrict sensitive apps only to corporate devices with perfect compliance.

- Device certificates are used in Transport Trust to establish mTLS (mutual TLS) connections, where both endpoints validate identity.

Tools that implement it:

- MDM/UEM: Intune, Workspace ONE, Jamf, FortiClient EMS

- Certificates: Internal PKI (Windows CA, OpenSSL), cloud services (Entra ID Certificate Authority)

- Posture checking: Endpoint agents that report status to a central server (Forticlient, WorkspaceONE, etc.)

User Trust (Verifiable Human Identity)

What it protects: Prevents unauthorized access based on stolen, shared, or compromised credentials. Single-factor authentication is no longer sufficient.

How it works: User identity must be validated with multiple factors and, depending on context, with greater or lesser friction.

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA): Something you know (password) + something you have (token, mobile app) + something you are (biometrics). The second factor makes stealing credentials insufficient.

- Certificate-based authentication: The user has a personal digital certificate. In combination with password or MFA, this adds another layer. Additionally, certificates can have short validity and renew automatically, reducing exposure windows.

- Passwordless (FIDO2, WebAuthn, Windows Hello): The logical evolution of MFA is eliminating the password completely. With FIDO2, the user authenticates with biometrics (fingerprint, facial) or local PIN, and the device signs a cryptographic challenge that validates identity without sending secrets over the network. There’s no password to steal, phish, or reuse. It’s more secure and more convenient than traditional MFA. Windows Hello for Business, passkeys on iOS/Android, and hardware tokens like YubiKey implement this standard.

- Contextual/adaptive authentication: You don’t always ask for the same thing. If the user connects from their usual device, during business hours, from the office, maybe passwordless is enough. If they connect from a new country, at 3 AM, from an unknown device, you require passwordless + additional identity validation (push notification with explicit confirmation, security question).

- Single Sign-On (SSO): You authenticate once (with MFA), and that identity token gives you access to multiple applications without asking for credentials again. This reduces friction without sacrificing security, as long as the initial authentication flow is robust.

Integration with other pillars:

- Device Trust + User Trust = complete context. You not only know who they are, but where they’re connecting from.

- Application Trust: Access policies can be by user AND by group. “The Finance team can access the ERP, but only if they’re authenticated with MFA and from corporate devices.”

- Transport Trust: The identity token (SAML assertion, JWT) is validated on every request. If the token expires or is invalidated (user disabled, permission change), access is cut off.

Tools that implement it:

- Directories: Active Directory, Entra ID, Okta, Google Workspace, WorkspaceONE

- MFA: Entra ID MFA, Duo, Google Authenticator, FortiToken, WorkspaceONE Verify, hardware tokens (YubiKey)

- SSO/Federation: SAML, OIDC, services like Okta, Entra ID, Workspace ONE Access

Transport/Session Trust (Communication Continuously Verified)

What it protects: Prevents man-in-the-middle attacks, session hijacking, and lateral movement after an initially successful authentication.

How it works: It’s not enough to authenticate at the beginning and trust the session for hours. Transport must be encrypted and the session must be continuously revalidated.

- Mandatory robust encryption (TLS 1.2+): All traffic between user and application must be encrypted. Nothing in plain text, not even on the internal network. Properly configure cipher suites, disable old TLS versions, validate certificates.

- Mutual TLS (mTLS): Not only does the server present a certificate; so does the client. This ensures both ends of the connection are who they claim to be. Common in microservices architectures and system-to-system communication.

- Short session times: An authenticated session shouldn’t last indefinitely. Configure reasonable TTL (time to live): 4-8 hours for regular users, less for administrative access. This limits the exploitation window if someone steals a session token.

- Continuous revalidation: During the session, periodically validate that the user and device still comply with policies. If the device stops meeting compliance (antivirus turns off, user disabled in AD), the session ends even if the token hasn’t expired.

- Micro-segmentation: Control traffic between internal resources (east-west traffic), not just inbound/outbound traffic (north-south). Each VM, container, or workload has its own network perimeter. Firewall rules apply by identity (user, AD group, workload identity), not just by IP. This prevents lateral movement: if an attacker compromises a web server, they can’t talk directly to the database unless an explicit rule permits it. Policies “travel” with the workload if it moves hosts or datacenters.

Integration with other pillars:

- Device Trust + User Trust: Device and user certificates are used to establish mTLS. Without them, no connection. In micro-segmentation with identity-based firewalls, these same certificates or authentication context allow the distributed firewall to know “this traffic comes from user X in group Y” and apply rules by identity instead of just source/destination IP.

- Application Trust: The gateway publishing the application validates the session token on each request. If the token is invalid or expired, it rejects the connection.

- Data Trust: Transport encryption protects data while traveling over the network. Even if someone intercepts the traffic, they can’t read it.

Tools that implement it:

- Reverse proxies: nginx, HAProxy, Traefik (with TLS/mTLS configuration)

- ZTNA gateways: FortiGate ZTNA, Zscaler, Cloudflare Access, Palo Alto Prisma

- Micro-segmentation: VMware NSX, Cisco ACI, Illumio, Calico (in Kubernetes)

- Session management: Managed by IdP (Entra ID, Okta) with conditional access policies

Application Trust (Granular Access and Principle of Least Privilege)

What it protects: Prevents lateral movement. If an attacker compromises an account, they shouldn’t be able to access everything, only what’s strictly necessary for that account.

How it works: Every application or resource must have explicit access policies. Not “if you’re on the network, you can access everything,” but “you have access only to what you need for your role.”

- Selective application publishing: Instead of giving VPN access to the entire network, you publish applications individually. The user connects to “app.company.com,” not “the entire 10.x.x.x subnet.”

- Identity and context-based access policies: It’s not enough with “user X can access.” It’s “user X, from a corporate device, with MFA, can access app Y between 8 AM and 6 PM, from these geographic locations.”

- Application-level gateways: A proxy or gateway in front of each application validates identity, device compliance, and permissions before letting traffic through. If something fails, traffic doesn’t reach the backend.

Integration with other pillars:

- User Trust + Device Trust: The gateway validates both before allowing access. Valid user + non-corporate device = access denied.

- Transport Trust: The connection between user and gateway is encrypted, and the gateway constantly re-validates session tokens. Thanks to micro-segmentation, at the network level transit is also restricted; if an attacker evades the Gateway they still can’t establish communication with an unauthorized workload.

- Data Trust: By limiting which applications each user can use, you also limit what data they can touch. If you can’t access the ERP, you can’t see the financial information living there.

Tools that implement it:

- ZTNA gateways: FortiGate ZTNA, Zscaler Private Access, Cloudflare Access

- Reverse proxies: nginx, HAProxy with integrated authentication

- Identity-based firewalls: Palo Alto, FortiGate with AD integration, Azure Firewall with user identity, VMware NSX with Identity Firewall

Data Trust (Protecting Information, Not Just the Perimeter)

What it protects: The data itself, regardless of where it is. It doesn’t matter if an attacker reaches the storage; if the data is encrypted and they don’t have the keys, it’s useless to them.

How it works: Information must be protected at rest and in transit, classified by criticality, and with granular controls over who can do what with it.

- Encryption at rest: Encrypted disks on endpoints (BitLocker, FileVault), encrypted storage on servers, databases with TDE (Transparent Data Encryption). If someone steals a physical disk or takes a VM snapshot, they can’t read the information.

- Encryption in transit: Already covered in Transport Trust, but worth emphasizing: data never travels in the clear.

- Information classification: Not all data is equal. Public, internal, confidential, restricted. Each level has different controls. This involves process (training users on how to classify) and technology (metadata in files, tags on storage objects).

- Granular permissions: Principle of least privilege in file shares, databases, APIs. Not “Everyone: Full Control.” It’s “the Finance group has read/write on this folder, the rest don’t see it.”

- Data Loss Prevention (DLP): Monitor and block exfiltration attempts. If someone tries to copy 10,000 customer records to a USB or upload them to personal Dropbox, the system detects and blocks it.

- Auditability: Logs of who accessed what, when, from where. If there’s an incident, being able to reconstruct what happened.

Integration with other pillars:

- Application Trust: Access policies limit which applications each user can use, which indirectly limits what data they can touch.

- User Trust + Device Trust: Only authenticated users from verified devices can decrypt information. Encryption keys can be tied to user/device certificates.

- Transport Trust: Transport encryption ensures data isn’t intercepted while traveling. Encryption at rest ensures that if someone steals it they still can’t read it.

Tools that implement it:

- Disk encryption: BitLocker, FileVault, LUKS

- Storage encryption: AWS KMS, Azure Key Vault, on-prem solutions with encrypted volumes

- DLP: Microsoft Purview, Symantec DLP, Forcepoint, open source solutions (MyDLP, OpenDLP)

- Classification: Microsoft Information Protection, Boldon James, manual labels + process

- Auditing: SIEM (Splunk, QRadar, Wazuh), native system logs (Windows Event Log, syslog)

How the Pillars Integrate

In a real Zero Trust implementation, the pillars don’t “execute” one after another like a checklist. They overlap, feed each other, and correct each other. Every access is a decision based on complete context.

Let’s take a concrete example: María accesses erp.company.com.

Same User, Trusted Context

María is during business hours, from her corporate laptop, in the office. The browser already has an active session.

The system evaluates identity (User Trust) and context: known user, usual device, expected location. It doesn’t ask for additional MFA. Not because it “trusts,” but because the risk is low and the friction cost doesn’t add real security.

The device presents its certificate (Device Trust). It’s valid, issued by the corporate CA, the equipment is patched and in compliance. That enables the next step.

The connection is established encrypted, with mTLS (Transport Trust). The gateway and device mutually validate each other. At the network level, micro-segmentation allows that specific flow: María → ERP gateway. Nothing else.

With all that context, the gateway evaluates policies (Application Trust): María belongs to Finance, is in an allowed context, accesses only the ERP. She doesn’t see other internal applications, even though they’re “on the same network.”

Within the ERP, permissions are those of her role (Data Trust). She can query and load information, but not massively export sensitive data. Everything is audited.

Access granted. Without unnecessary friction. Sufficient security for the real risk.

Same User, Intermediate Context

María needs to access the ERP from home, outside business hours, because she was asked to close something urgent.

Identity is valid (User Trust), but the context is no longer ideal: different location, home network, atypical hours. The system doesn’t block, but raises the requirement level. It asks for explicit MFA, even though it normally wouldn’t, and the session has a shorter TTL.

The device passes validation (Device Trust), but with restrictions. It’s her corporate laptop, it’s in compliance, it has valid certificates, but access is marked as “medium risk.” That feeds the rest of the decisions.

The connection is established encrypted with mTLS (Transport Trust), but micro-segmentation is stricter: only the exact flow to the ERP is enabled. No auxiliary services.

At the gateway, access policies (Application Trust) allow the ERP, but in restricted mode. María can query information and complete the specific task, but certain actions are blocked: mass exports, structural changes, administrative access.

Data remains protected (Data Trust): any attempt to copy sensitive information outside permitted channels is logged or automatically blocked. Everything is audited, in more detail than in normal access.

Access exists, but it’s not equal to ideal access. It’s sufficient to solve the problem, without opening more attack surface than necessary.

Same User, Untrusted Context

Now let’s change only the context: María tries to access erp.company.com on a Saturday at dawn, from a country she’s never been to, using personal equipment.

Identity is still valid (User Trust), but the context isn’t. The system requires strong MFA, and even so the device doesn’t pass validation (Device Trust): it’s not registered, there’s no machine certificate, no known posture.

Access is blocked before the application even comes into play. It doesn’t matter that the password is correct. It doesn’t matter that the user is “trusted.” The context isn’t.

And even if someone managed to pass that stage, the network doesn’t help either: from that location and segment, traffic doesn’t even reach the gateway (Transport Trust).

Result: access denied. No discussion.

What Matters Isn’t the Flow, It’s the Decision

Zero Trust isn’t about doing more steps, it’s about making better decisions with complete context:

- User Trust says who they are.

- Device Trust says from where.

- Transport Trust ensures the conversation is legitimate and controlled.

- Application Trust limits what they can access.

- Data Trust defines what they can do with the information.

When all that integrates well, two interesting things happen:

- In healthy contexts, the experience is simple.

- In odd contexts, the system restricts possible compromises.

It’s not magic, it’s not automatic to implement, it’s not free in complexity. But when it works it enables workflows with little friction and an elevated security posture.

The Foundations: Visibility and Analytics, Automation and Orchestration, Governance

The five pillars are the visible components of Zero Trust, but for them to function three cross-cutting capabilities are necessary. They’re not pillars themselves, but requirements that allow everything else to operate.

Visibility and analytics: You can’t protect what you don’t see. Zero Trust requires complete visibility of traffic (who accesses what, from where, when), device status, active identities, and sensitive data. But visibility without context is noise; you need the ability to correlate events: “this user authenticated from three different countries in 10 minutes” isn’t an isolated data point, it’s a compromise indicator. Tools like SIEM (Splunk, Microsoft Sentinel, Wazuh), XDR platforms (Microsoft Defender XDR, SentinelOne Singularity), or vendor-specific solutions (Omnissa Intelligence, FortiAnalyzer) consolidate logs and generate actionable alerts.

Automation and orchestration: Manually validating every access, reviewing every device’s compliance, adjusting firewall rules when a user changes roles—these aren’t scalable actions. Zero Trust needs automation: automatic provisioning/deprovisioning of access (identity governance), automatic remediation when a device loses compliance (force antivirus update, revoke certificate), automatic incident response (isolate compromised device, terminate active sessions of affected user). SOAR (Security Orchestration, Automation and Response) like Cortex XSOAR, FortiSOAR, or native UEM/XDR platform capabilities make this possible. Without automation, operational overhead prevents implementing complete Zero Trust.

Governance: Someone has to decide who can access what, under what conditions, and who’s responsible for keeping those policies updated. Governance includes: identity lifecycle management (onboarding, role changes, offboarding), periodic access reviews (does this user still need access to this system?), documented and auditable policies, and separation of duties (who approves access isn’t who technically configures it). Identity Governance and Administration (IGA) tools like Entra ID Governance or Okta Identity Governance, or well-defined processes with workflows in systems like ServiceNow or Jira, are part of this. Without governance, Zero Trust degrades: orphaned permissions, users with more access than necessary, policies nobody maintains.

Conclusion: Zero Trust is Architecture, Not Checklist

Zero Trust is not a binary state you reach and you’re done. It’s an architecture model you apply gradually, prioritizing where it matters most. The fundamental change isn’t in being able to check all items on a checklist, but in how you think about access design: never trust by default, always verify, grant the minimum necessary privilege.

The five pillars—Device Trust, User Trust, Transport Trust, Application Trust, Data Trust—work together. None is sufficient by itself. And without the foundations of visibility, automation, and governance, it doesn’t matter what tools you have, you won’t be able to sustain it over time.

This doesn’t solve everything. Legacy applications still exist that don’t understand modern authentication and for which we must be creative and still won’t achieve 100% integration. Users also still exist who find creative ways to break the rules. And the risk still exists that someone steals credentials + device + certificate, although it’s harder. Zero Trust narrows the window of opportunity for an attacker, but doesn’t close it completely. Whoever promises you otherwise is selling you something impossible.

Finally: if after reading this you’re left thinking “okay, I understand the concept, but how do I start?”, in the second part of this article I talk about concrete implementation: how to evaluate your current stack, what you can do without buying anything, and when you do need budget. Because understanding the architecture is the first step. The next is starting to apply it.

References

NIST SP 800-207 – Zero Trust Architecture

Foundation document of the Zero Trust model.

https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-207/finalBeyondCorp: A New Approach to Enterprise Security (Google)

Practical origin of many current Zero Trust ideas. Interesting more for the approach than the concrete implementation.

https://research.google/pubs/pub43231/Zero Trust Networks: Building Secure Systems in Untrusted Networks – Evan Gilman, Doug Barth

A book that explains Zero Trust without turning it into a vendor catalog.

ISBN: 978-1491962190CISA Zero Trust Maturity Model

Useful for understanding Zero Trust as a gradual process and not as a binary state.

https://www.cisa.gov/zero-trust-maturity-modelMicrosoft Zero Trust guidance (conceptual)

Beyond the Microsoft stack, the principles and scenarios are well explained if read with judgment.

https://www.microsoft.com/security/business/zero-trustCloudflare – What is Zero Trust?

Good introductory explanation. Valid as reference as long as you separate the model from the product.

https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/security/glossary/what-is-zero-trust/